Recently, there was an excellent post about iBuyers from Homebloq, a company that appears to sell some sort of a mobile app “connecting Chicago brokers and buyers” according to the website. The blog is not signed, but I think it’s written by Austin James, the co-founder of Homebloq, and is titled, “How iBuyers Die.”

I’ve seen a lot of these kinds of posts and sentiments since Opendoor pioneered the space in 2014, but this one caught my eye and kept my interest because the author spent a good amount of time and effort, did his/her homework, and put together an interesting bear case against iBuyers.

The author ultimately concludes that “It’s not looking great for iBuyer economics” but doesn’t take a strong stance. He leaves a bunch of outs with a lot of questions, writing:

Let’s tally this up. It’s not looking great for iBuyer economics. Again, there is so much here to discuss that we’ve not yet covered. What if agents choose to eliminate dissemination of listings to iBuyer sites? What if Amazon acquires OpenDoor? What if a recession hits and wipes out the cash accounts and strangles profit margins for long enough to bleed out the iBuyers? What if I’m flat our wrong?

Since it appears that Austin is a fan of Notorious, and I’m becoming a fan of his, I wanted to take some time to address a number of the issues he raises. Ultimately, it isn’t that I disagree with Austin or think that his bear case is wrong, but that I want to caution him and the rest of the industry against wishful thinking.

It’s one thing to look at the challenge of iBuyers (and the related challenge of the institutionalization of real estate) with clear eyes, acknowledging uncomfortable realities, and then trying to formulate a response. It’s a whole other thing to look at the challenge, pick and choose what you want to see, in order to tell yourself pretty lies about how ultimately, you’re going to be just fine.

So let’s get into it.

The Economics of iBuyers

Many of you already know that I’ve been covering and talking about iBuyers pretty extensively, including a full-length Red Dot report in 2018. While I am a bull on iBuyers, I think I’m pretty realistic about the economics of iBuyers.

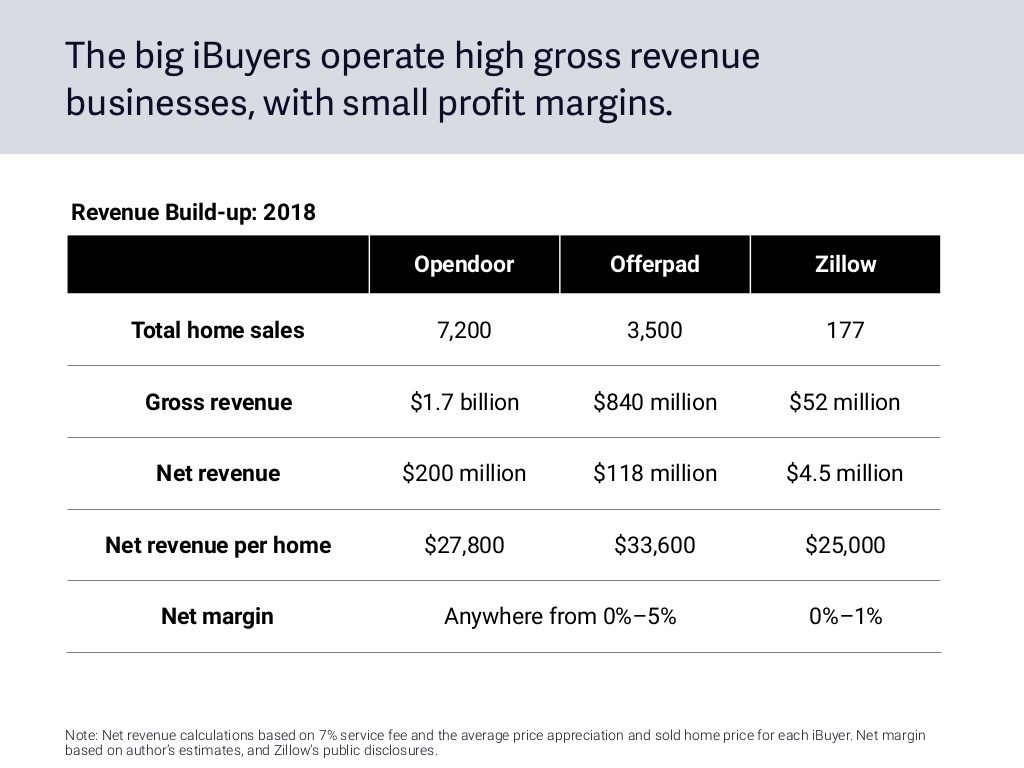

Here’s the thing: the only real data we have about the economics of iBuyers comes from Zillow, which reported its unit economics for 2018. Everybody else, from Opendoor to Offerpad to Redfin to Flyhomes or Knock or anybody else, has revealed nothing. We get drips of information from agents in the field whose clients have received offers from various companies, mostly to talk about how much of a ripoff such lowball offers are, but we don’t know what that means at the company level.

I did appreciate that Austin referenced Mike Delprete’s work on iBuyers, which is the best in the business. And I find nothing to disagree with Austin or Mike on the findings:

I just want to point out that the small font “Note” at the bottom is meaningful. MikeD’s numbers are estimates and reasonable calculations based on reasonable assumptions. Only Zillow’s numbers are reliable at this point.

So Austin makes a few points on the economics:

- iBuyers have low margins in a highly cyclical business;

- iBuying is capital intensive; and

- iBuying is “hypercompetitive.”

Let’s get into these.

Low Margins + Highly Cyclical

I look at that and wonder, iBuyers have low margins compared to whom? Brokerages? It’s the worst kept secret in real estate that brokerages have such tiny profit margins that all of them rely on metrics like agent count and sales volume and transactions and market share in order to play hide-the-ball on the most important metric of all: profitability.

Realogy, the one traditional brokerage that reports publicly, posted sub-1% EBITDA margins in 2018 after spending all of 2018 focusing on, you guessed it, profitability. If Austin or anybody else is going to claim that iBuyers have crappy margins compared to brokerages, he’s going to have to post some reliable numbers.

As it happens, I do have some reliable numbers from brokerages (none of which I can share, unfortunately). And I know for a fact that just about every brokerage I’ve looked at would be staring bankruptcy in the face if the CFPB made one rule change tomorrow prohibiting affiliated businesses. I can relate that I spoke to one brokerage owner at Inman earlier this year, who told me that his brokerage operations with over 1,000 agents (which makes him a very large brokerage in real estate), generated $12,000 in profits. You read that right: twelve thousand dollars in total profits. If it were not for his affiliated escrow and title businesses, he’d be closing his doors.

So yes, iBuyers have low margins. We all know that. Rich Barton talked about aiming for 200-300 basis points in profit for Zillow’s iBuying business, and that’s probably being aggressive. The published Zillow numbers show 0.6% profit margin (or 60bps) on each iBuying transaction in 2018.

My take is, “So what?” Nobody else has much in the way of profit margins either.

The same goes for the cyclical nature of real estate. It isn’t as if brokers and agents don’t operate in the same cyclical business that iBuyers do. The same players are fighting over the same piece of the commission pie in traditional brokerage too. The market will go up and the market will go down, and some brokers and agents will go out of business, while others will survive and thrive.

So this paragraph makes very little sense to me:

Unlike Amazon, iBuyers may not have the velocity and frequency of transactions necessary to develop brand loyalty or dominance in their environment the way Amazon does. Even Amazon’s profit margins are slim, averaging between 0–4% annually since 2009. With Zillow’s margins on it’s iBuying program generally 0–1% and others up to 5%, adding the costs of scale, competition, and general fee compression across the industry, there is little room for error to achieve economies of scale necessary for long term success.

Three reasons why.

First, why are we comparing iBuyers to Amazon? I mean, if we’re comparing unrelated industries, why not Tesla? Apple? Online sports betting?

Second, I can’t figure out how and why the “costs of scale, competition and general fee compression” leaves little room for error to achieve economies of scale necessary for long term success. Who are we pointing to as the paragon of long term success here? Realogy? HomeServices of America? Re/Max? Obviously not Redfin, since Austin bashes Redfin for its low market share numbers.

Third, is there some industry out there where there is a lot of room for error to achieve economies of scale? Is there any business where you can screw up time and again and still find huge success? I don’t know of a single example of any company anywhere bumbling its way into fortune and dominance.

Capital Intensive

Yes, iBuying is capital intensive. No one denies that. But it’s another case of, “So what?”

You know what other businesses are capital intensive? Oil and gas. Mining. Agriculture. Pharmaceuticals. Wireless telephony. Auto manufacturing. And many of those industries feature small profit margins to boot. What does that have to do with anything?

Throwing in Compass as some example of how investor capital doesn’t mean real growth seems like an odd red herring to a discussion about iBuyer economics since… well… Compass isn’t one and has stated that it doesn’t intend to become one.

Hyper-Competitive

The first thought I have here is, “Hyper-competitive compared to what?” Local MLS services? Absolutely. Compared to brokerage services? Not a chance. To be an iBuyer, a company needs (a) massive amounts of capital, (b) sophisticated data analysis, (c) groundwork for execution (i.e., inspection, repairs, the transaction itself, etc.), and (d) lead flow. The first two requirements all but guarantee that only a few companies can compete.

In brokerage? To be a real estate broker, a company needs (a) a broker’s license, and (b) agents, and in some states, (c) an office.

The Proper Analogy: Market Makers

Truth is, most of the mistakes around thinking about the economics of iBuyer stems from the fact that people see them as real estate companies, or as flippers/investors. From 2014, when Opendoor first hit the scene, I’ve thought of iBuyers as something else: market makers.

From the August 2018 Red Dot on iBuyers:

The market maker system evolves from the convergence of iBuyers as more liquidity is injected into the system.

A seller can sell his house to an iBuyer and buy his house from an iBuyer. The iBuyer in turn sells that old house to someone else, who has sold her house to an iBuyer. And the cycle continues.

One of the effects of iBuyers is that they begin to influence the price.

Any offer to purchase has to be higher than Opendoor’s; otherwise, the seller would simply take Opendoor’s offer. And given the amount of its sales activity, the sales comps will start reflecting Opendoor’s pricing on the sale side.

Over time, the Bid and Ask prices of iBuyers become one of the most important comps for all buyers and sellers.

The market makers effectively set the price of houses, hence the name: they make the market.

So when Rich Barton says, “Ideally I would like to have the Zestimate be a live offer for every house in the country,” I interpret that as meaning, “The Zestimate will be the Bid price.”

The profits and economics of market makers are fairly simple and straightforward. From the Investopedia article on market makers in electronic trading:

For example, let’s say that a market maker has entered a sell order for Microsoft (MSFT) and the bid/ask is $65.25/$65.30. The market maker can try to sell shares of MSFT at $65.30. If this is what the market maker chooses to do, he or she can then turn around and enter a bid order to buy shares in MSFT. The market maker can bid higher or lower than the current bid of $65.25. If he or she enters a bid at $65.26 then a new market is created (referred to as making a market) because that bid price is now the best bid. If the market maker attracts a seller at the new bid price of $65.26 then he or she has successfully “made the spread.” The market maker sold 1,000 shares at $65.30 and bought these shares back at $65.26. As a result, the market maker made $40 (1,000 shares x $0.04) on the difference between the two transactions. This might not seem like much, but doing this repeatedly with larger order sizes can provide lucrative profits. All day long market makers do this, providing liquidity to individual and institutional investors. The major risk for the market maker is the time lapse between the two transactions; the faster he or she can make the spread the more money the market maker has the potential to make.

However, making money from the differences in bid and ask prices is not the only function of market makers. Their first priority is to provide liquidity to their own firm’s clients, for which they will receive a commission. They may also facilitate trading for other brokerage firms, which is very similar to the duties of a specialist.

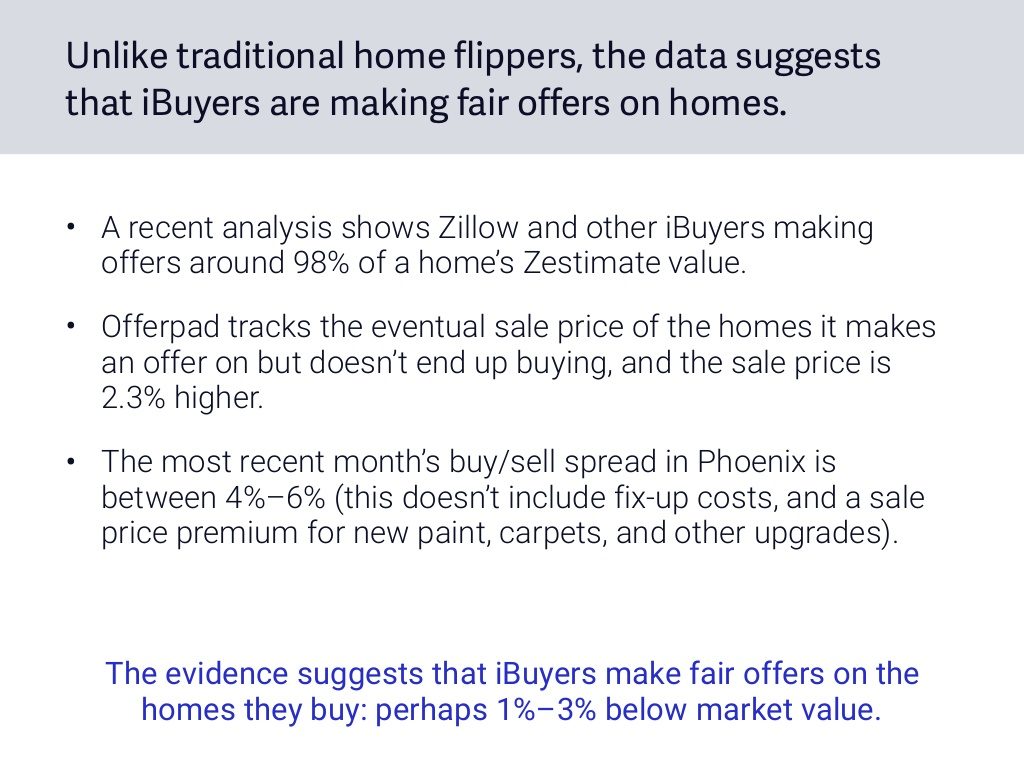

We’ve already known that iBuyers like Opendoor and Zillow try to make a spread. Mike DelPrete’s iBuyer report says that iBuyers charge a 6%-10% service fee to the seller and have 3%-8% price appreciation. I interpret that as “commission for providing liquidity” and “bid-ask spread.” Furthermore, DelPrete has some data on specific companies:

The Bid-Ask spread with today’s iBuyers might be 1-3%. That isn’t investing. It isn’t flipping. It’s market making.

Accordingly, all of the issues that Austin brings up are issues… but not really issues, if you think about it. Market makers in every market require enormous amounts of capital, make tiny margins per-trade, and have competition. Trading is highly cyclical to boot: ask anybody who trades stocks, bonds, or commodities for a living.

So Mike DelPrete is absolutely correct when he points out that the iBuyer business model really only works at scale. So does any kind of market maker business model.

Implications of the Economics

Once you shift your mindset into understanding iBuyers as market makers in housing, the implications clear up.

For investors, the question isn’t whether you want to invest in a real estate company or a proptech play. The question is whether you want to take a chance on a market maker in a highly illiquid commodity/product. The only things less subject to commoditization than houses might be people and some kinds of art.

For the industry, the question really isn’t Redfin’s market share or the spread between bid and ask, but what role if any you have in a world of market makers. There is precious little that the industry can do to affect the rise of housing market makers (I’ll go into that in a future post) so the real question is how brokers, agents, MLSs, tech companies, and the like adjust to their emergence.

But like the title says, if you’re going to make good decisions, you can’t tell yourself pretty lies about what’s going on.

-rsh

1 thought on “[VIP] Don’t Tell Yourself Pretty Lies About iBuyers, Part 1: Economics of iBuyer”

Comments are closed.